In this project, I compare the tree cover loss in the strictly protected parks and less protected parks in Malawi, using Hansen et. al’s data set. This dataset represents global forest change at 30 meters resolution. Particularly, this project sought to determine the percentage of tree cover lost within the strictly versus less strictly protected parks in year 2019.

According to the analysis, less protected parks experienced more tree cover loss than their strictly protected counterparts (Figures 1a-c). Given that these areas are marked as “less protected,” this outcome is unsurprising and aligns with the assumptions of a less protected area (defined below). Specifically, strictly protected parks lost 0.039% of tree cover, while less protected parks lost 1.87% of tree cover. However, while the tree cover loss is higher, this does not necessarily mean that there was more deforestation. According to the Global Forest Watch, “loss of tree cover may occur for many reasons, including deforestation, fire, and logging within the course of sustainable forestry operations.” Thus, while deforestation may be a reason for the tree cover loss, it is important to keep in mind that there are numerous other reasons for tree cover loss and that these two phrases are not synonymous.

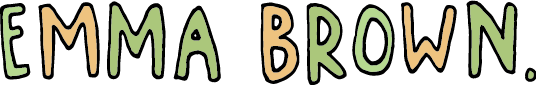

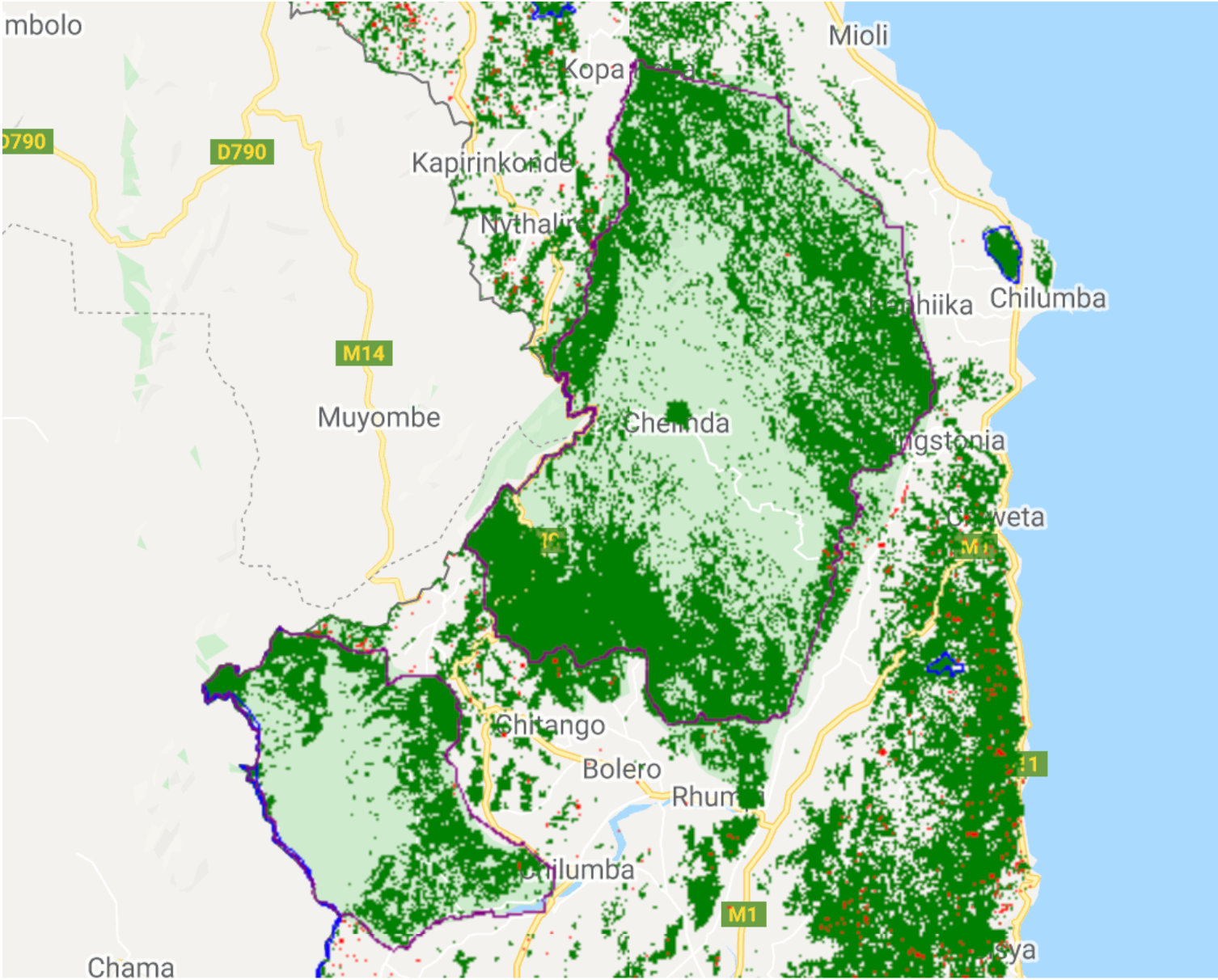

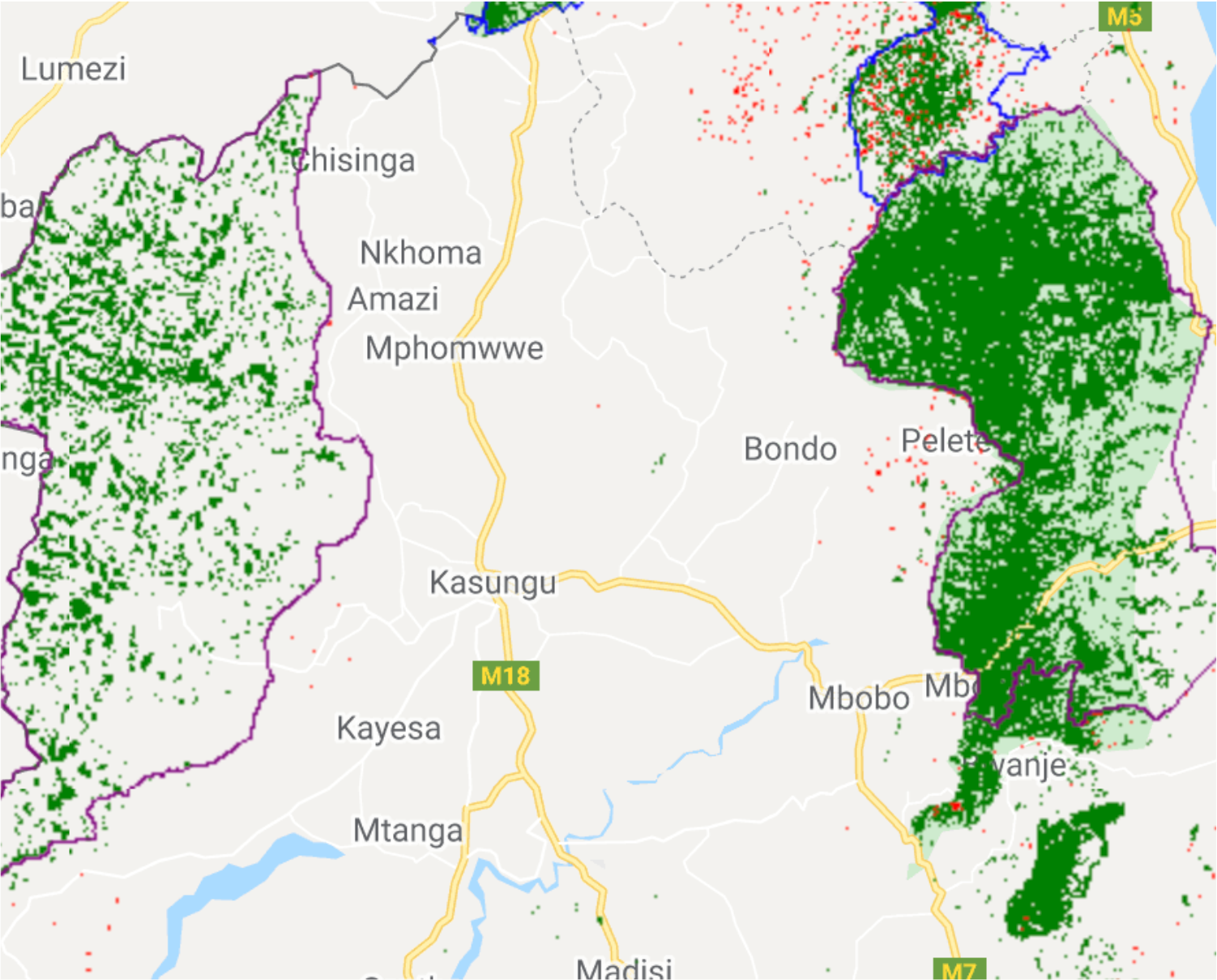

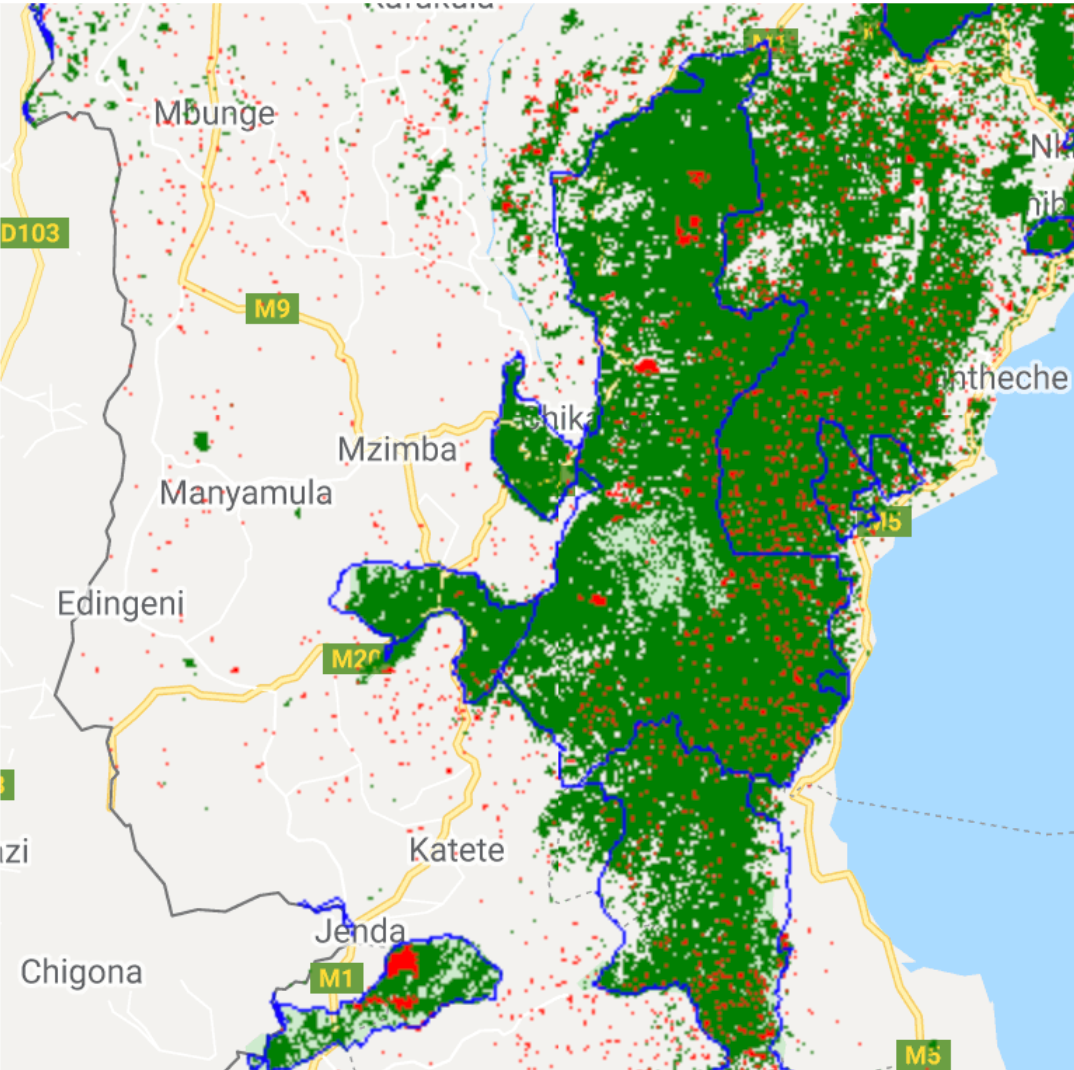

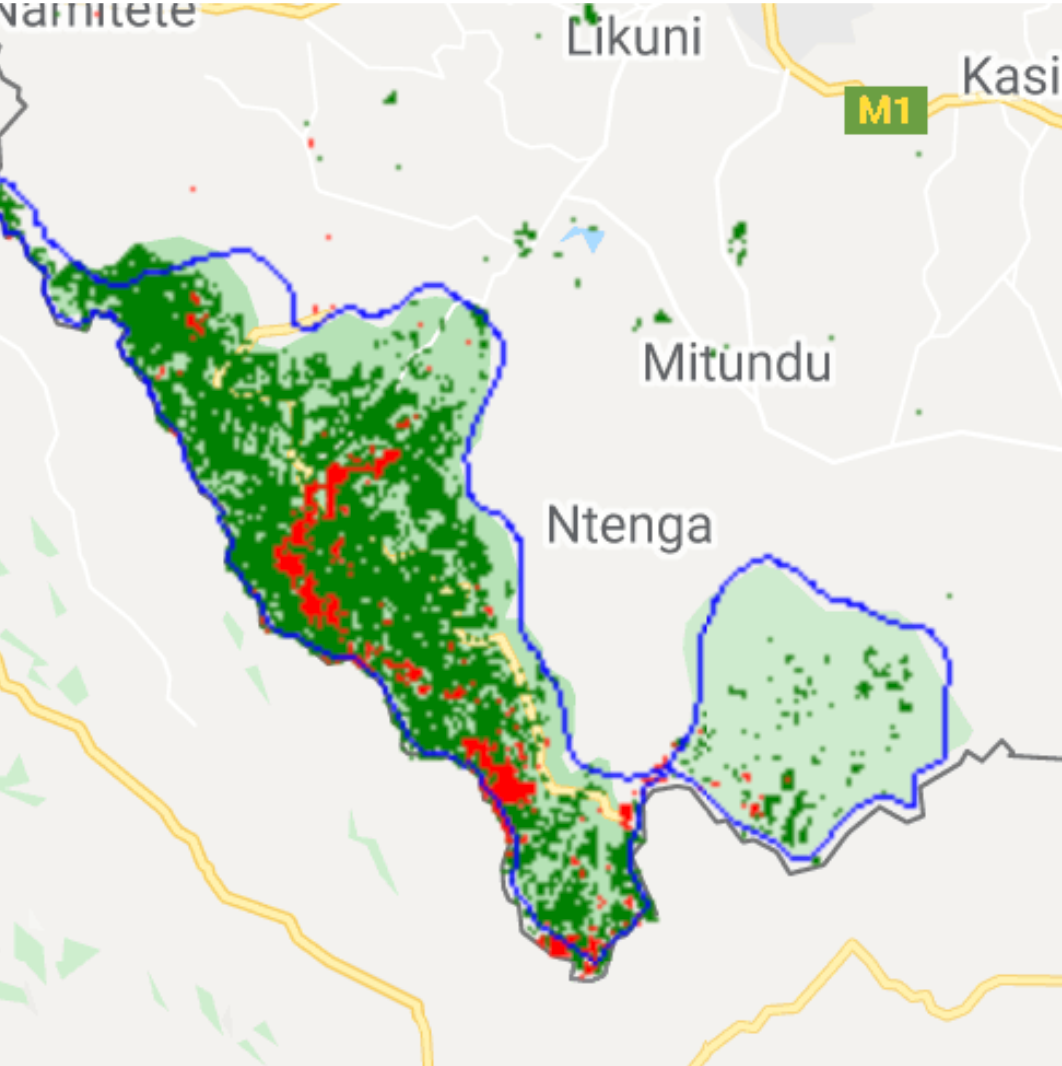

Figure 1a) A map of Malawi showing the strictly protected areas (shown in purple), less protected areas (shown in blue), as well as areas with greater than 30% tree cover in 2000 (green) and forest cover loss in 2019 (red). The map illustrates that there is more forest loss in areas designated as “less protected.”

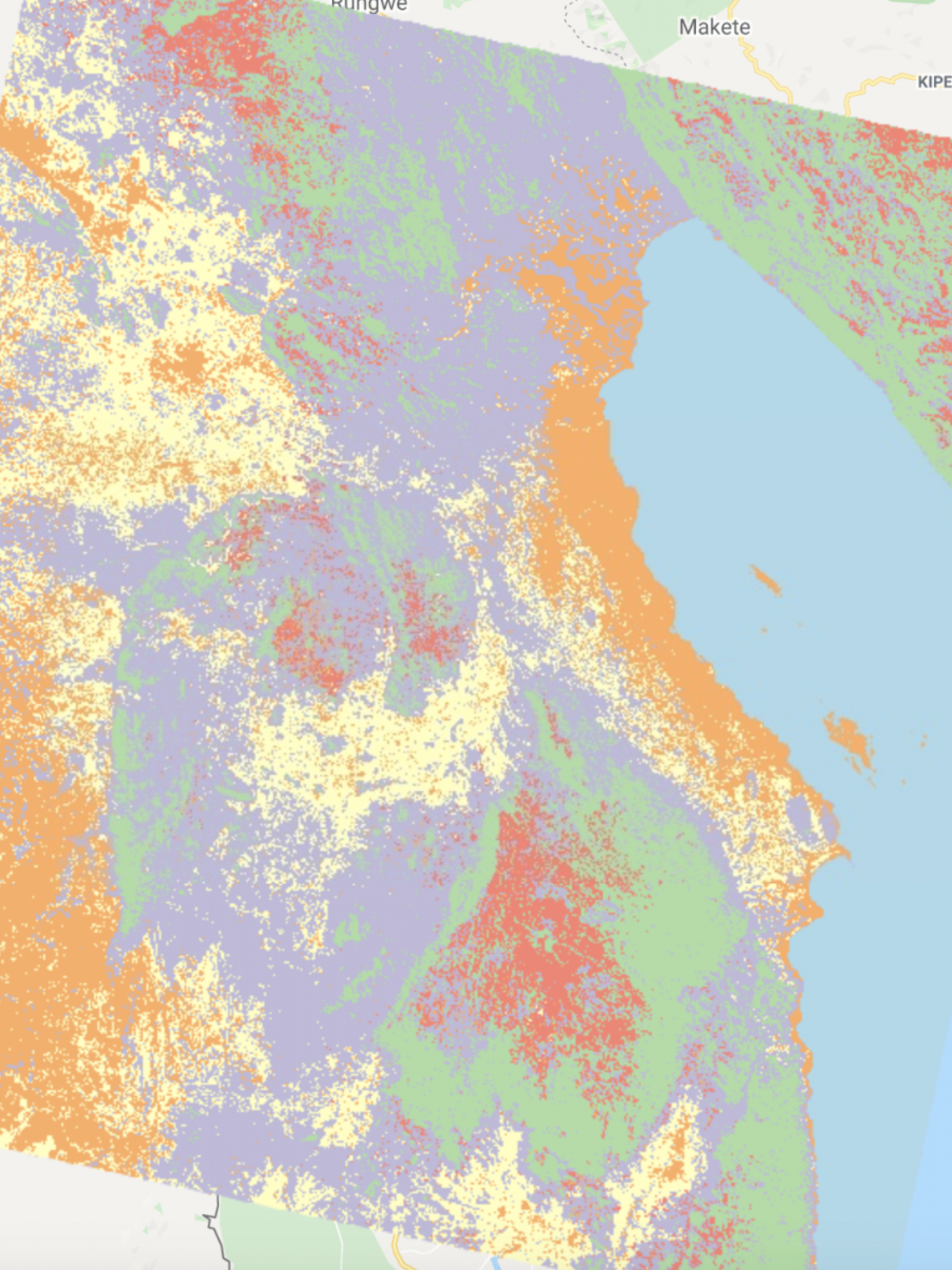

Figures 2b) A closer look at the strictly protected areas (outlined in purple). As you can see, there is little to no tree loss in these areas (red).

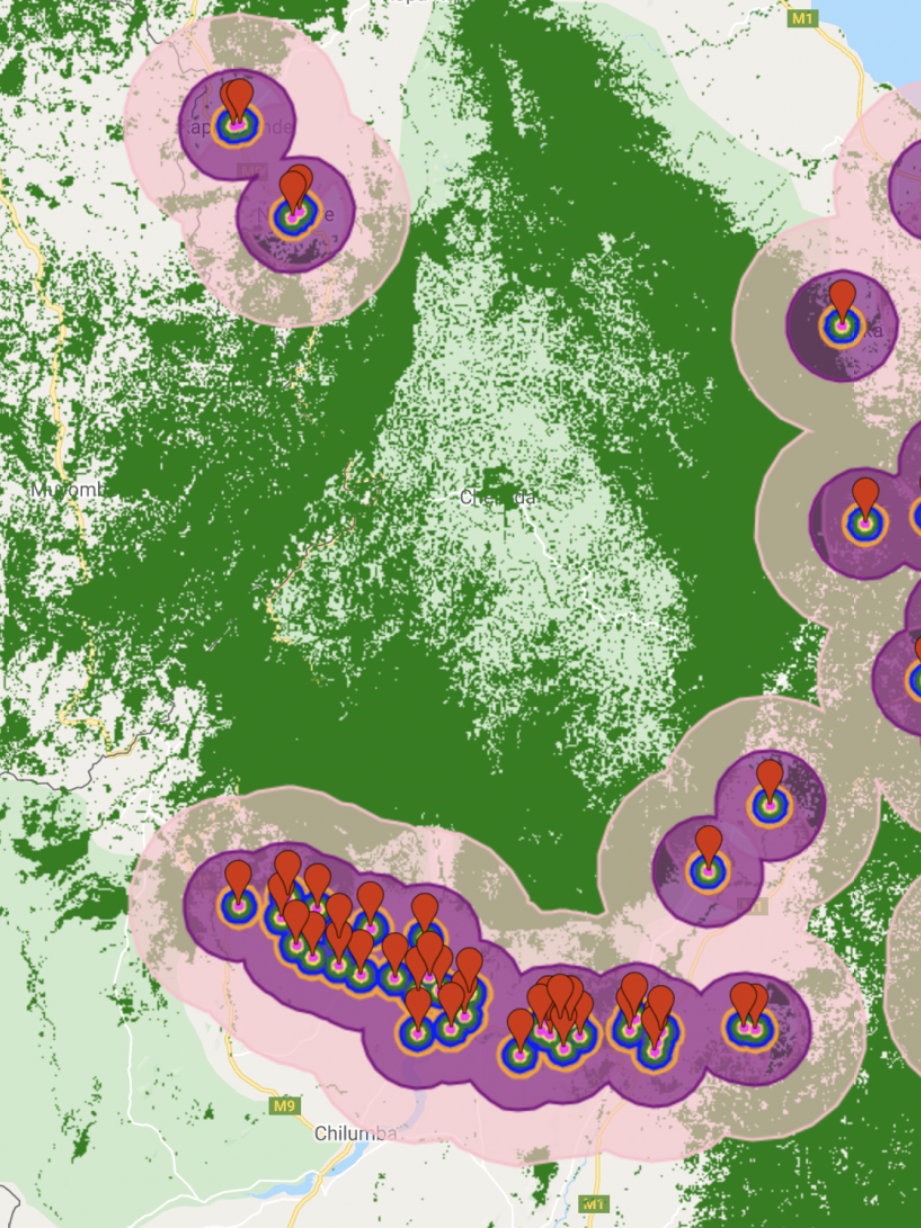

Figures 2c) A closer look at the less protected areas (outlined in blue). As you can see, there is far more tree loss in these areas (red) compared to the strictly protected areas.

Defining Strictly vs. Less Protected Parks

For the ease of analysis, parks were divided into “strictly protected” and “less protected”. Strictly protected parks were classified as areas with an IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) management category of 1a (Strict Nature Reserve), 1b (Wilderness Area), II (National Park), III (Natural Monument or Feature), or IV (Habitat/Species Management Area). Less protected parks were classified as areas with an IUCN management category of V (Protected Landscape), VI (Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources), “not reported” or “not applicable,” as well as parks with a “proposed” status.

While these categories help us better organize our data, there are assumptions made that limit our understanding of the results. For example, an IUCN category of “not reported” or “not applicable” does not imply or automatically mean that the area is less protected, and classifying a proposed park as a less protected park prematurely defines a protected area before it is truly “protected.” Lastly, there is no strict definition of “protected” that these categorizations are based off of. What are they protected from? Does the sustainable use of a forest (category VI) automatically write-off the area as “not-protected” even though they are used sustainably by those whose livelihoods rely on these areas? The analysis overlooks the intricacies of the land cover and use and may generalize details.

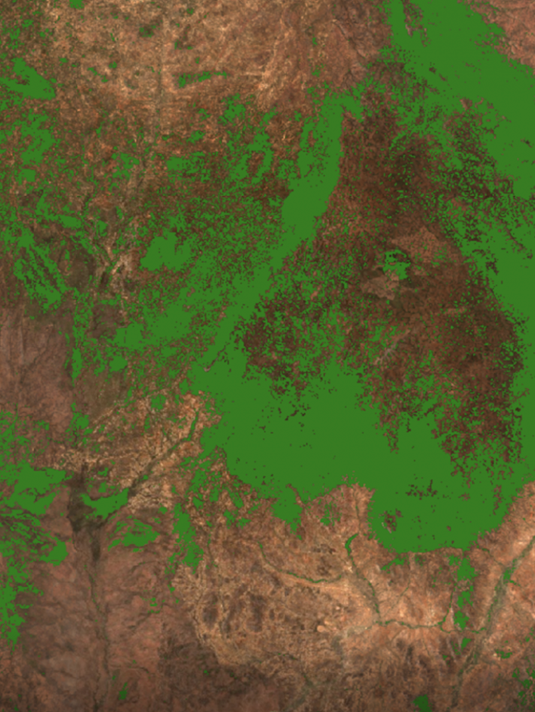

Defining Tree Cover

The definitions that Hansen et al. uses may also lead to problematic conclusions. Hansen includes agricultural areas in their designation of tree cover, which can be misleading — as seen on Global Forest Watch (which utilizes the Hansen data), tea plantations are counted as tree cover, which experience cyclical loss or gain depending on the season. Thus, the tree cover encompasses a wide variety of areas with differing land use, some of which are intentionally planted for the purpose of harvesting, thus loss/gain can fluctuate greatly depending on the land use. Forest loss is defined as “a stand-replacement disturbance or the complete removal of tree cover canopy at the Landsat pixel scale.” The specificity of “complete” removal of tree cover canopy can lead to misleading conclusions in our analysis as the binary categorization of forest loss can overlook areas with partial forest loss. Again, forest loss can also be very intentional — such as tree plantations that are planted for the purpose of future removal, and then to be re-planted again. This can lead to misleading conclusions as often forest loss is associated with the permanent removal of trees, and may exclude the cyclical and intentional removal of tree cover.

Link to the code in Google Earth Engine